I love to grow my own food. And what I love most about planting, harvesting, and cooking all that food is knowing every vegetable that lands on my plate has a story behind it. The lettuce that started from a speck of seed and turned into a season of salads. The squash that survived a bout of powdery mildew and grew into an armful of beautiful butternuts. The artichoke that stood alone in the first year and eventually divided into a dozen more plants.

But beyond those stories that started in my garden are the ones that go back a hundred or even a thousand years when you hold a packet of heirloom seeds in your hands.

What is an heirloom? The word denotes something of value, whether monetary or sentimental, handed down from generation to generation. If your house caught on fire, what would you pack up? Perhaps family albums, works of art, or antique jewelry. Your ancestors, on the other hand, probably would have saved their seeds. And that’s one of the most intriguing things about heirloom seeds.

Imagine a variety of fruit or vegetable that was so important to your family history or homeland that you would bring it with you when you immigrated to the New World. Such is the case with Old Greek Melons, which were introduced in the early 20th century when Greek immigrants settled in Utah for mining jobs. Or Hutterite Soup Bush Beans, which arrived in North America in the 1870s when Hutterite Christians fled persecution in Europe.

Then there are the heirlooms that have been grown, saved, and passed down through several generations of the same family, like Bedwell’s Supreme White Dent Corn, which was originally cultivated in Clarke County, Alabama, and preserved by the Bedwell family for at least a century. Or Missouri Pink Love Apple Tomatoes, which have survived since the Civil War. The Barnes family grew these tomatoes as an ornamental, believing (as many people did at the time) that tomatoes (or “love apples”) were poisonous. Of course, we now know that isn’t true.

Read more: The 30 Best Tasting Heirloom Tomato Varieties (By Color!)

Some heirlooms are named after the people, places, or events that they’ve become synonymous with. There are the tragic stories, like the Cherokee Trail of Tears Pole Bean. Without knowing any of its history, you’d likely guess there was a lot of pain and suffering — and there was.

The Trail of Tears left thousands of Cherokee Indians stricken with disease, exposure, starvation, and death as they were relocated from their tribal lands and forced to march through the Smoky Mountains to the Indian Territory in present-day Oklahoma. One of the precious possessions they carried with them to their new home was this prolific pole bean variety, a slender green pod yielding shiny, jet black beans.

Other stories, however, are more hopeful, like that of the Mortgage Lifter Tomato. In the 1930s, MC “Radiator Charlie” Byles was a radiator repairman in Logan, West Virginia, as well as an amateur tomato breeder. He decided that he wanted to build a better tomato, a large and meaty variety that could feed families.

The famous tomato was bred by crossing four of the biggest tomato varieties he could find: German Johnson, Beefsteak, an unknown Italian variety, and an unknown English variety. He selected and cross-pollinated his strongest plants for six years before he finally stabilized the new breed and developed his dream tomato.

People would drive hundreds of miles to buy his tomatoes, which sometimes weighed up to 4 pounds each! By selling his seedlings for $1 (a rather hefty sum in those days for a little plant), Radiator Charlie was able to pay off his $6,000 mortgage in six years. (Here’s an interesting radio segment about the history of the Mortgage Lifter.)

There are also stories that harken back to a page in American history we would never learn from our history books otherwise, like the Fish Pepper and its significance in the African-American community in the late 1800s. Or the varieties that come to us by chance from other cultures, like the Fife Creek Cowhorn Okra, an heirloom that has been in the Fife family since the 1900s. It was believed to have been given to them by a Creek Indian woman who stayed with the family for a year in Jackson, Mississippi.

Seeds also come to us by way of explorers, like Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker, a renowned British botanist (and Charles Darwin’s closest friend) who discovered the Sikkim Cucumber in the Eastern Himalaya in 1848. Calling the cucumber “Sikkim,” after the Indian state where he found it growing, Hooker wrote in one of his texts, “So abundant were the fruits, that for days together I saw gnawed fruits lying by the natives’ paths by the thousands, and every man, woman and child seemed engaged throughout the day in devouring them.”

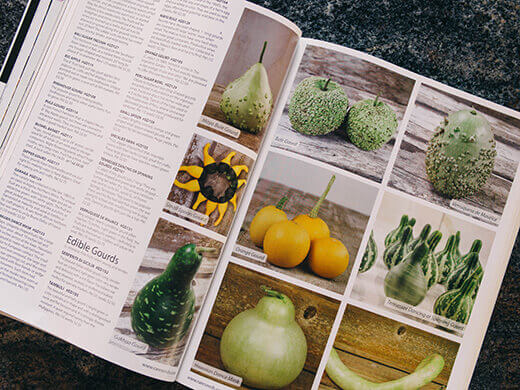

With the season of seed catalogs in full swing, I can’t help but bury myself in all those pages filled with wonderful pictures of beautiful old varieties from all over the world. One of my favorite catalogs is the behemoth from Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. Over 350 pages! I may be a little biased here — I wrote two articles for The Whole Seed Catalog, which is a special edition of their annual catalog that’s part seed catalog, part magazine. (You can buy a copy on their website, at your local newsstand, or from Whole Foods Market.)

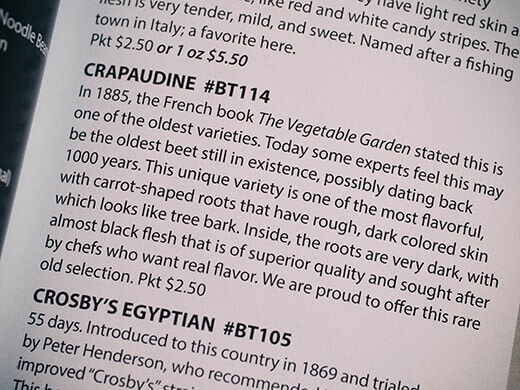

It’s where I learned about the Crapaudine, believed to be the oldest beet still in existence and dating back 1,000 years. It certainly looks like no beet I’ve ever seen in a market; the roots are carrot-shaped with dark, rough skin resembling tree bark. I grow this variety almost every year and it serves up some of the sweetest flesh I’ve tasted in a beet.

It’s also where I became fascinated with the history of heirloom seeds. A lot of the descriptions read like little history lessons. Many of them traveled thousands of miles before they were brought into mainstream seed collecting, and some of them are listed in Slow Food’s Ark of Taste, a database of heritage foods at risk of extinction.

I love weaving all that history together with mine when I make a meal with food I’ve grown myself from seeds I’ve saved and sowed for years. I love knowing that the memories made from that food add to the stories behind those seeds, even if the only people to ever know those stories are the ones I’ve shared my meal with.

Though I often order from Baker Creek, there are many other small seed houses that do wonderful work in preserving old varieties and keeping them free from genetic modification. Sadly, their numbers are far below the thousands of seed catalog companies that used to exist between the 1880s and the First World War, a period known as the golden era of seed catalogs and hand illustrations.

I encourage you to support a local seed library or seed supplier this year. Here are a few that specialize in heirlooms:

- D. Landreth Seed Company

- High Mowing Organic Seeds

- The Living Seed Company

- Mike the Gardener’s Seeds of the Month Club

- Salt Spring Seeds (Canada)

- Seed Savers Exchange

- Southern Exposure Seed Exchange

- Sustainable Seed Company

- Terroir Seeds

- TomatoFest

- Victory Seed Company