Maybe it was my Asian upbringing that taught me never to waste food, as my family used and ate every part of the vegetable, fish, chicken, pig, or cow that we brought home.

Or maybe it’s my ever-growing curiosity when it comes to food from the land… but when I walk around the garden, looking at all my thriving plants, I always think, Can I eat that?

And by “that,” I mean the unconventional parts of the plant that you typically don’t think to eat. This was how I came to love artichoke stems, leek greens, and cucumber leaves, parts that are normally discarded or composted, but are in fact quite tasty.

Worth a read: 11 Vegetables You Grow That You Didn’t Know You Could Eat

So one day, when I was walking by my tomato plants, I started wondering whether the leaves were edible or not.

With vines that sometimes grow to 10 feet long, it seemed like such a waste that the leaves weren’t used when the amount of fruit seemed so small in proportion.

It got me thinking… Why don’t we eat tomato leaves?

Popular culture has taught us that tomato leaves are part of the “deadly nightshade” family and thus, they must be poisonous. But I bet that more than a few people, if asked, would have no idea what that even means. It’s just what’s known. No questions asked—but we need to ask.

What is a nightshade, why are the leaves poisonous but not the fruit, and why don’t we see bunches of leaves in the supermarket if they aren’t poisonous?

Let’s take a look at all the myths surrounding the Solanaceae family and explore the science that says otherwise.

Myth #1: Nightshades are highly poisonous, so tomato leaves must be poisonous too.

When referring to the Solanaceae family of plants, many people call it by its more common moniker, the nightshade family.

Within this family are the vegetables we know and love, like tomatoes, tomatillos, potatoes, eggplants, and sweet and hot peppers.

But also within this family are the nightshades famously known to be toxic to humans, like black henbane, mandrake, and the “deadly nightshade,” also known as belladonna (Atropa belladonna).

Despite its nickname, belladonna, an herbaceous perennial, has historical use in herbal medicine as a pain reliever and muscle relaxer, a treatment for stomach and intestinal issues, and even as a beauty aid.

In fact, the name “bella donna” means beautiful lady in Italian. It comes from the outdated practice of women putting drops of belladonna berry juice in their eyes to dilate their pupils. The look was considered attractive in the day!

But rest assured that though tomatoes are distantly related to belladonna, they do not contain the chemical compounds that make belladonna (especially its berries) so poisonous.

The tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) does have an interesting history however, as its scientific name, lycopersicum, is Latin for “wolf peach” and derives from German folklore.

When the tomato was brought to Europe in the 16th century, people believed it to be poisonous like other members of the Solanaceae family. Legend had it that witches used these hallucinogenic plants in potions to conjure werewolves. Since the tomato plant’s fruit looked so similar to that of belladonna, it was dubbed the wolf peach.

You see, tomatoes of yore looked nothing like the plump, juicy, fashionable tomatoes we know and love. Before modern cultivation, tomatoes grew wild in the Andes and they were tiny—the size of a blueberry. Their shape and color were often mistaken for belladonna berries.

These days, we know that while tomatoes belong to the (very large and diverse) nightshade family, they definitely aren’t of the deadly nightshade variety.

This ambivalence was later reflected in the tomato’s other accepted scientific name, Lycopersicon esculentum (translated to “edible wolf peach”).

As you can see, the bad rap bestowed on tomatoes is simply an old wives’ tale, left over from a less-informed era.

Myth #2: Tomato leaves contain toxic compounds called alkaloids.

As mentioned in my previous post on carrot tops, all vegetables contain alkaloids. Alkaloids are part of a plant’s defense mechanisms (existing in all parts of the plant to protect against certain animals, insects, fungi, viruses, and bacteria) and we consume them on a daily basis in various amounts.

That locally-grown heirloom bean and kale salad you had for lunch? Alkaloids. Those antioxidant-rich organic green smoothies you make every week? Major alkaloids.

While it’s true that some alkaloids are not good for you (like nicotine and cocaine), others can be good or bad, depending on your view (like theobromine, the stimulant found in chocolate, or caffeine, that Monday-morning life-giver).

Even though alkaloids are present in your everyday veggies, you could never eat enough of them in one sitting for the alkaloids to be harmful.

So what gives with tomatoes?

The major glycoalkaloid in the tomato plant is tomatine. (To put it simply, a glycoalkaloid is an alkaloid bonded with a sugar.)

Tomatine exists in all green parts of the plant, including the stems, leaves, and green tomatoes.

(For the sake of clarity, whenever I mention “green tomatoes” in this post, I’m referring to the immature, unripened green tomatoes—and not the varieties of naturally green tomatoes.)

A study published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry found that the highest concentrations of tomatine were found in senescent leaves, followed by the stems, fresh leaves, calyxes, green fruits, and finally, the roots (which had the lowest concentrations).

The difference in concentration between the fresh leaves and green fruits is negligible, so one isn’t necessarily “safer” to consume than the other. While tomatoes do show a decline in tomatine content as they mature and ripen, no one has ever thought twice about devouring a heaping of fried green tomatoes or pickled green tomatoes!

Recipe to try: Roasted Green Tomato Salsa Verde

Glycoalkaloids are also poorly absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract of mammals, and will pass through quickly to the urine or feces. In people who are sensitive to these compounds, stomach irritation may occur but they would have to ingest an unrealistic amount of green tomatoes or tomato leaves to experience ill effects.

So what’s the deal? Are tomato leaves poisonous or not?

Disclosure: If you shop from my article or make a purchase through one of my links, I may receive commissions on some of the products I recommend.

In the book Toxic Plants of North America, the authors wrote that a toxic dose of tomatine for humans would appear to require at least a pound of tomato leaves, and that “the hazard in most situations is low.”

According to this food safety study (which compared the potential toxicity of glycoalkaloids found in tomatoes, potatoes, and eggplants), tomatine is a relatively benign glycoalkaloid. It resulted in no significant changes to liver weight or body weight when fed to mice, and is not considered adverse to human health.

Another study has shown tomato leaves and tomato stems to have higher antioxidant activity and polyphenols (plant-based micronutrients that help fight disease and improve overall health) than tomato fruits.

What’s most surprising is the discovery of tomatine as a cancer inhibitor. The glycoalkaloid has been found to effectively kill or suppress the growth of human breast, colon, liver, and stomach cancer cells.

This study suggests that consumers could benefit from eating high-tomatine green tomatoes, and that there may be a “need” to develop high-tomatine red tomatoes as well (for the treatment of cancer and/or the study of tomatine as an anti-carcinogenic and anti-viral agent).

Judging from these studies, and the lack of evidence that tomato leaves are toxic for human consumption, I’ll have to give Myth #2 a miss.

Myth #3: Dogs have died eating tomato leaves, so they’re definitely poisonous.

Somewhere along the way, you may have heard a story of someone’s dog dying because it ate a bunch of green tomatoes or tomato leaves. But is this cause for concern for you?

Here’s the deal: tomatine can be deadly for a dog if eaten in large quantities.

And the last part of that sentence is key—in large quantities.

Whether or not tomato leaves can kill a dog is very much a dose-dependent issue. As most pet owners know, dogs eat all kinds of crazy things and don’t really know when to stop.

If they have unrestricted access to your garden and haven’t been trained to stay away from plants, it’s very possible they’ll chow down all your tomatoes, leaves and all.

For small dogs, especially, this amount of ingestion can cause diarrhea and vomiting at best, or a hospital visit in the worst-case scenario. This goes for many other plants in your house and garden, not just tomato plants.

(The list of plants that are toxic to dogs is long and surprising: lemongrass, chamomile, tarragon, borage, milkweed, purslane, and various parts of apples, peaches, and grapefruits.)

Does toxicity to a dog equal toxicity to humans? Far from it.

There are other foods we eat freely that are known to be poisonous to dogs, such as chocolate, grapes, raisins, garlic, and onions. But the substances that are harmful to dogs don’t do the same damage to humans.

To date, there’s scant evidence in veterinary literature regarding the toxicity of tomato leaves. One study in Israel examined the possibility of livestock poisoning by feeding tomato vines to cattle for 42 days, but found no ill effects.

Myth #4: Organic gardeners make tomato-leaf sprays to kill pests, so that must mean tomato leaves can kill us too.

Tomato-leaf sprays are made by chopping and soaking tomato leaves in water, then using the sprays on various plants to control aphids.

Since tomatine, a glycoalkaloid, has fungicidal properties and is part of the tomato’s natural defenses, it makes sense that the compound could potentially protect against pests when extracted into a solution.

But theoretically, you could make a spray with any green part of the plant, like the stem (which contains even higher amounts of tomatine).

Unless you’re allergic to tomatoes, the tomatine in tomato-leaf sprays won’t harm you—and that’s why it’s used as an organic method of pest control.

Read more: Get Rid of Pests With This 2-Ingredient Homemade Insecticide

Myth #5: Tomato leaves aren’t sold commercially and no one has ever cooked with them, so that’s a sign they’re not meant to be eaten.

True, if you tried to Google recipes for tomato leaves, you aren’t likely to find any. In his book Cooking by Hand, former Chez Panisse chef Paul Bertolli included a recipe for leafy tomato sauce.

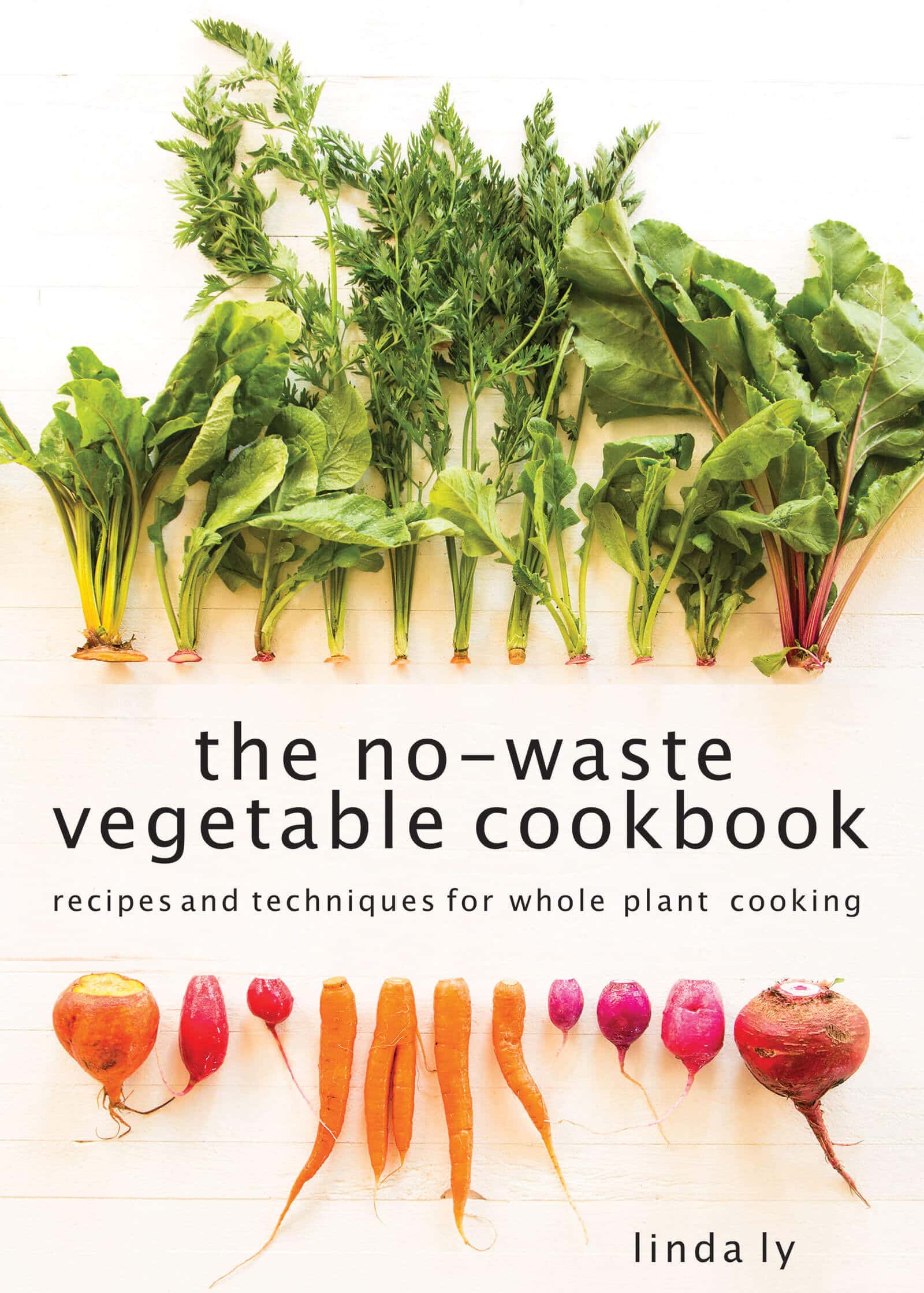

In The No-Waste Vegetable Cookbook, I have my own version of a spicy minty tomato sauce infused with tomato leaves, as well as tomato leaf pesto that’s delicious on pizza and sandwiches. Aside from those examples, however, not many people have stepped up and ‘fessed up to their culinary use.

But—and a big but—that does not mean they aren’t edible.

Until I started traveling to other countries, exploring their local cuisines, and cooking from my garden, I never knew all the possibilities of the plants I was growing.

(If you live anywhere outside of North America, you’re probably shaking your head at what we throw out!)

How else can you cook with tomato leaves? I’ve found it best used as an infusion so you can really capture the essence of a ripe summer tomato. Try infusing a handful of tomato leaves in olive oil (I love it as a drizzle on a Caprese salad) or infusing the leaves in tomato juice when you make gazpacho.

Another favorite technique is tossing thinly sliced tomato leaves with a bit of fish sauce, and using it as a savory garnish for rice or fish. Gently fried whole leaves of tomato also make a tasty topping for pasta, the way you’d fry sage leaves in browned butter. Dehydrated and crushed tomato leaves can be used as seasoning, perhaps folded into pizza dough or sprinkled over noodles.

Waste less food. Get more nutrition. All with the same vegetables you already know and love.

The No-Waste Vegetable Cookbook is your guide to everything edible from all the plants you grow or buy — things you might not have known you could eat.

As for the rest of my garden, an adventurous appetite has led me to discover how delicious broccoli leaves are (you won’t find many recipes for those either), as well as carrot tops, nasturtium pods, radish pods, radish greens, and pea shoots (which are actually an Asian grocery staple).

Learning how to use the entire plant is my favorite “lazy gardening” strategy because it means I can get more food out of my garden with a lot less work.

The fact that tomato leaves aren’t part of the mainstream American diet doesn’t make them toxic by any means. People just don’t know what to do with them… yet. (Hopefully this will change in my generation.)

You know what is toxic though? The amount of food we waste in this country, and how Americans lead the world in food waste.

Conclusion: So, can you eat tomato leaves?

Contrary to popular opinion, yes—tomato leaves are flavorful, fragrant, and 100 percent edible. You can cook the fresh, young leaves like most other sturdy garden greens, such as kale, collards, or cabbage (leafy greens that need a little longer cooking time to become tender).

But personally, I like to use tomato leaves as an accent, where their strong herbal aroma adds a unique depth of flavor that you can’t get from tomato fruits themselves.

More tomato growing posts to explore:

- Grow Tomatoes Like a Boss With These 10 Easy Tips

- How to Grow Tomatoes in Pots—Even Without a Garden

- How to Best Fertilize Tomatoes for the Ultimate Bumper Crop

- How to Repot Tomato Seedlings for Bigger and Better Plants

- Why and How to Transplant Tomatoes (a Second Time)

- Planting Tomatoes Sideways: How Growing in a Trench Results In Bigger Healthier Plants

- Florida Weave: A Better Way to Trellis Tomatoes

- Conquer Blossom End Rot and Save the Harvest

- Can You Eat Tomato Leaves? The Answer Will Surprise You

- Why Tomato Leaves Have That Unique Smell

- The Power of Fermenting and Saving Tomato Seeds

- 4 Fastest Ways to Ripen Tomatoes in the Garden and Beat the First Frost

- The 30 Best Tasting Heirloom Tomato Varieties (By Color!)

- 83 Fast-Growing Short-Season Tomato Varieties for Cold Climates

- The Best Time to Pick Tomatoes for Peak Quality (It’s Not What You Think!)

This post updated from an article that originally appeared on August 20, 2013.

View the Web Story on eating tomato leaves.