It’s been three weeks since the passing of our Easter Egger hen, Gisele, and while I’ve finally accepted her death, her memory is still a little sad to process.

I think the situation struck me especially hard because she was the first pet I ever lost and I know she won’t be my last; the unfamiliar experience of caring for (and eventually euthanizing) a terminally ill pet was scary, to say the least.

And afterward I cried for Gisele, cried for her sisters, and cried for my pugs (who will soon be 11 and 12 years old) over the inevitable and uncontrollable. I know this is all part of the circle of life, and I think (hope) I’ve become stronger as a result of all this… one of our many lessons in life.

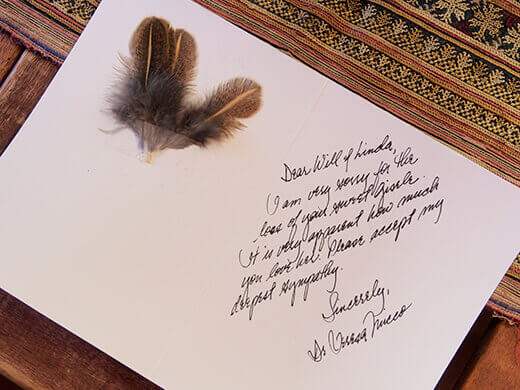

I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart, truly and deeply, for all the beautiful, thoughtful, heartfelt, compassionate, and uplifting emails and comments I’ve received since my original post. I read every single note. So many of you shared your own stories about losing furry or feathery children and offered the most amazing support I could ever hope for.

Your emails gave me strength and in some ways, even made me smile.

I know it’s often difficult to find the right words to comfort someone, especially a virtual stranger, but please know that even a small sentiment means a lot. I am so grateful to those of you who reached out this past month.

After Gisele’s passing, we (our vet) sent her body to the California Animal Health & Food Safety Laboratory System at UC Davis, which offers a free necropsy (an autopsy performed on an animal). The service is meant to monitor the health and well-being of backyard flocks and make sure backyard-spawned diseases won’t affect the state’s poultry industry.

The preliminary results came back within a day or two as inconclusive. The final report (sent a week later) listed the cause of death as lymphoid leukosis.

Lymphoid leukosis is an avian viral disease typically transmitted from an infected mother to her unborn chick.

The vet believed Gisele became infected while she was still inside the egg. The virus has a long incubation period (four months or more), so she was sick for some time before she started showing symptoms.

Initially, the vet suspected Marek’s disease as the symptoms are quite similar, though Marek’s usually runs it course within the first six months of life.

Lymphoid leukosis manifests itself in older chickens around the time of sexual maturity (Gisele was two years old).

Chickens become pale (on their combs and in their beaks), emaciated, depressed, and progressively weaker to the point where they lose full mobility. It’s a devastating disease to watch unfold.

Unlike Marek’s disease, lymphoid leukosis is not spread by air. In a flock, the virus can spread by bird-to-bird contact and by physical contact with contaminated environments. Infected chickens lay infected eggs and produce infected feces.

If a healthy chicken eats the infected egg (or feces) and she’s genetically susceptible, she could contract the virus.

I have never seen my chickens eating each other’s eggs or feces, and I keep the coop and surroundings fairly sanitary on a day-to-day basis, so I hold out hope that Kimora and Iman were not infected. At present, they appear peppy and happy and hungry and curious… all good signs of healthy chickens.

I have to wonder, though, if Gisele was lowest in the pecking order because the other two knew she was sick. Their bullying became a bit more intense in the last few months; they often tried to keep her away from their food and I had to give her a separate dish to make sure she was eating.

Was it like World War Z, where they had a sense she was terminal and stayed away from her?

Currently there is no vaccination and no treatment for lymphoid leukosis. Once a chicken becomes infected, it’s a terminal disease that’s not easily diagnosed until after death.

In a way, I’m sort of relieved to learn this, only because it assures me that her death occurred naturally.

For a while I was torn on whether I should’ve kept her in the hospital longer or whether I did the right thing in putting her to rest. Knowing that her cause of death was genetic — and not an airborne contagion, or something I could have prevented — eased much of my worry and guilt. Only time will tell with my other two hens.

Thank you, again, for keeping me — and all of us — in your thoughts.

Hello there, Linda. I stumbled upon your blog, and specifically, your posts about sweet Gisele. I know these posts are old, but I have to thank you for the comfort they have given me tonight. I came home Sunday morning and found one of my Easter eggers, Ginger, dead on the ground inside the coop. Your Gisele looks SO much like Ginger, so your photos are bittersweet to look at. My 97 year old farmer Grandfather did an unofficial necropsy, and said it looked like she’d had a blood clot, and that her liver didn’t look quite right. It breaks my heart, and like you, I thought of the “what ifs,” and thought to myself “how did I not notice something was wrong.” Just the day before she was happily pecking around and being her usual self. Her sister Rosemary is my pride and joy – I nursed her back to health at three months old after she’d hurt her leg in a coop-moving accident. I see the way you spoil and love your chicks, and to see that you’ve been able to move on with a new flock is truly inspiring. People think it’s crazy the way I spoil my chickens. I’m glad to know I’m not alone! Please tell me that eventually the sadness gives way to happy memories, as right now I feel so discouraged and I find myself worrying obsessively about my other 5. I am thankful to have stumbled on your blog tonight!

My heart goes out to you. It does get easier as time goes on, and my best advice is to continue loving on your other chickens and giving them the best life possible. Spoiling them and watching their silly antics is what helped me mourn and heal. While no chicken could ever “replace” Gisele, I recently brought home a new Easter Egger (4 years after losing Gisele) and am so happy to have her in the flock. She reminded me why I love Easter Eggers so much, as her temperament is very similar to Gisele, and just this week she laid a beautiful blue egg! She’s the first of the new girls to start laying — just like Gisele when I brought home my original flock in 2011.

Know that you and Ginger were very lucky to have each other, and the special relationship you have with all your chickens (and any new ones you may raise in the future) is what makes life so meaningful.

Hi Linda, I’m new to your blog, but love all the information you provide. This topic is particularly important as most of the folks I have communicated with regarding chicken illnesses simply say “if they get sick, cull them!” While I understand the sentiment (if you are a breeder with over 100 chickens, you don’t have the time or funds to take every one to the vet), it occurs to me that this approach lends nothing to our understanding of chicken health and illness. I hear a lot of criticism of Back Yard Chicken owners being too attached to their chickens, fussing over them, and making them pets, but it occurs to me that it is the Back Yard Chicken owners that are helping to make the most strides regarding chicken health and wellness because they love their chickens so much that they are willing to learn more about what keeps them healthy, spend the time to keep them that way, and spend the money on veterinary care when needed. Thank you for sharing this story, and thank you for all your posts. You have a very interesting and informative blog that is making a difference to those of us who what to increase our knowledge of these wonderful animals.

That’s so true what you say… backyard chicken keepers really are making strides in understanding, diagnosing, and treating chicken ailments. It is a great movement on so many levels, for food and animal husbandry alike.

Linda, My husband and I became chicken guardians this summer. Although we have cats and dogs and birds that live with us that we love very much, we had no idea how much these little ladies would move into our hearts! Yes, without a doubt, they each have their own personalities, likes and dislikes, quirks and idiosyncrasies. I just found your website this week, via Pinterest, and want to send my condolences to you on your loss of Gisele. I am so sorry for your loss. Best to you and the other girls. HUGS!

Thank you Michelle! That means a lot.

RT @theGardenBetty: The final results from UC Davis’ poultry necropsy: A Heartfelt Thank You and Gisele’s Diagnosis http://t.co/PMBt6eKX1C …

The final results from UC Davis’ poultry necropsy: A Heartfelt Thank You and Gisele’s Diagnosis http://t.co/PMBt6eKX1C #homesteading

Much gratitude for keeping me (and my remaining flock) in your thoughts. A Heartfelt Thank You and Gisele’s Diagnosis http://t.co/K60b7RR5Fm

Three weeks since the passing of my beloved hen: A Heartfelt Thank You and Gisele’s Diagnosis http://t.co/EuoDareRMR #homesteading

Brian Morris liked this on Facebook.

She was a great chicken.

A significant learning experience from this last month: A Heartfelt Thank You and Gisele’s Diagnosis http://t.co/ZrWZyZ9DTJ #homesteading

Sorry for your loss

Thank you.

For those of you who’ve asked, an update on my hen’s necropsy: A Heartfelt Thank You and Gisele’s Diagnosis http://t.co/1FoawSSLs5

Thank you for sharing this with us, I imagine it’s difficult for you. May your loss feel less painful over time, replaced with pleasant memories of your Gisele.

It’s nice to have a definitive answer on what happened to Giselle. Every animal I’ve lost has been to old age or a tragic accident except one. My pomeranian just fell over dead before her 5th birthday. I didn’t have the money for a necropsy at the time and I admit, her death still bugs me the most. I still miss my little one terribly… Currently, my eldest dog is almost 12 and she’s not doing too well – I’m going to have to make that decision sometime soon and I’m not looking forward to it – it never gets easier. However, I cherish the time I have with her and she knows she’s loved.

I’m glad we decided to get a necropsy because not knowing would’ve bugged me too, but at the same time, I was afraid the results would show the cause as possibly being my fault (and affecting the other hens as well). It was a nerve-wracking week on many levels.

thanks for keeping us informed with the result. Yes, it is always a heartache experience of growing and watching our beloved pets get old, Misha (my dog) is 11.5 this year and she has definitely started to show signs of aging and I am praying every day that she could live happily and healthy for just another year, a day later, I would be praying for another more year …

I thought I was going to lose one of my pugs about a year ago, but a change in diet did wonders for her physically and emotionally. She has hip dysplasia and lost use of both her back legs, but she still zips around the house happily like she’s got all fours!

awww Giselle was fortunate to have some people who loved her as much as you do.

Thanks for the kind words.

Amber Snow liked this on Facebook.

Ali Nazario liked this on Facebook.

Tyn Atol liked this on Facebook.

Laura Morrow Jacobs liked this on Facebook.

I’m glad you were able to get a diagnosis. Hopefully the other chickens will stay healthy for many more egg laying days ahead.

I hope so! I love those little ladies.

A Heartfelt Thank You and Gisele’s Diagnosis:

It’s been three weeks since the passing of our Easter Egger hen… http://t.co/rn8zwoxNXT

Blogged on Garden Betty: A Heartfelt Thank You and Gisele’s Diagnosis http://t.co/Z32OrxDZYA