“Can you eat them?” is the question I’m inevitably asked when we find dense mats of mushrooms growing up from our wood chip mulch after a good rain.

And while these ones look quite showy and fleshy, you’d easily walk by them without a second glance.

Each mushroom is no more than the size of a pinky nail, just a few millimeters wide and tall. In their immature state, the mushrooms are inconspicuous nubs with spiky or fluted sides, fully enclosed to protect the “eggs” inside.

As they age, the caps rupture to reveal a nest of eggs denotive of the mushrooms’ common name: bird’s nest fungi.

What is bird’s nest fungus?

Bird’s nest fungus—the mushroom—is not the same bird’s nest in Chinese bird’s nest soup (which are actual birds’ nests from the edible-nest swiftlet and black-nest swiftlet).

Bird’s nest fungi are part of the Nidulariaceae family of fungi, known for their stemless, rounded, hollow fruitbodies that resemble egg-filled birds’ nests. They include Nidularia, Nidula, Mycocalia, Crucibulum, and Cyathus.

The fungi that show up most frequently in my garden are Cyathus striatus, which have flared, tan-colored cups (called sporocarp) holding flattened, dark gray “eggs” (called periodoles) that are shaped like lentils.

They are excellent decomposers and thrive in damp, woodsy environments, often appearing in shady vegetable gardens or woody mulched paths. As long as the climate is temperate with intermittent rains, bird’s nest fungi can spread through any decaying organic matter they come in contact with.

Related: What IS That?! Dog Vomit Fungus: The Weird Slime Mold in Your Garden

You’ll find groups of bird’s nest fungi in dead tree trunks, rotted timber, wood mulch, bark chips, sawdust, decaying vegetation, or humus-rich soil, especially in fall. You’ll even see them pop up in animal dung, as the periodoles can survive a journey through the digestive tracts of cows and horses.

The life cycle of bird’s nest fungus

Bird’s nest fungi are not only fascinating in appearance, but fascinating in their reproductive strategy. They multiply through the “eggs” in their cups, but not in the way you might think.

Up close, the eggs are almost metallic looking, resembling shiny river stones. They’re known as periodoles, and they serve as protective sacs for the mushroom’s spores.

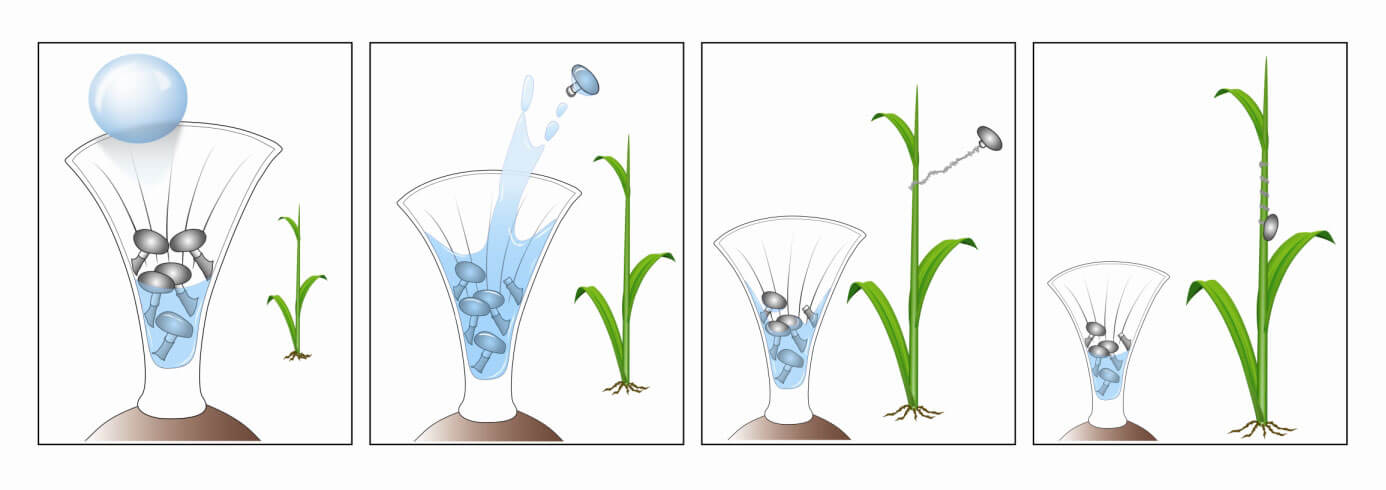

When drops of water from rain or irrigation land in the cups, they eject the periodoles up to four feet away—hopefully to hospitable terrain where they can reproduce.

At the scale of several millimeters, even a single raindrop can exert enough force to launch the periodoles like a water cannon. This unique method of dispersal is why you’ll sometimes hear bird’s nest fungi referred to as “splash cups.”

This is where it gets really interesting: Each periodole is connected to a funicular cord, essentially a long, fine thread with a sticky tail that unwinds several inches. Yes, inches. From that tiny cup!

As the periodole sails through the air, the cord may come in contact with, say, a blade of grass or a twig. It gets caught by its tail and rapidly wraps around the grass, much like a high-flying game of tetherball.

Here it remains until the periodole dries, then splits open to release the spores.

When the spores germinate, they grow into branching filaments called hyphae. The mass of hyphae (called mycelium) weaves through moist woody debris and consumes the wood to fuel its growth.

Bird’s nest fungi are saprophytes (microorganisms that live on dead organic matter) and this natural process is largely how wood decomposes.

When two different mating strains of mycelia fuse together, they form a new bird’s nest fungus that takes nutrients from organic waste and breaks it down rapidly (speeding up decomposition by two-fold.) This cycle usually occurs between July and October.

Having bird’s nest fungi in the garden makes it much easier and quicker to clean up plant debris, since they reduce large chunks into slivers that eventually decay and help enrich the soil.

Is bird’s nest fungus edible?

At a span of just a centimeter across, bird’s nest fungi are considered inedible due to their tiny size, though no study has ever shown them to be poisonous.

Harold J. Brodie, a Canadian mycologist who studied bird’s nest fungi extensively, concluded in his 1975 book, The Bird’s Nest Fungi, that the mushrooms were “not sufficiently large, fleshy, or odorous to be of interest to humans as food,” though some species have been used by native peoples to stimulate fertility.

The 1910 publication Minnesota Plant Studies suggests they are “not edible owing to their leathery texture.”

So we’ll give this species a miss, as there are far more satisfying (and delicious) mushrooms you can harvest in the wild.

How do you get rid of bird’s nest fungus?

Of all the fungi present in a garden, bird’s nest fungus is one of the most beneficial because of its natural composting abilities. It isn’t harmful to humans, dogs, wildlife, or living plants, so control measures aren’t necessary.

But if the “eggs” become a nuisance (sticking to surfaces like cars, houses, or other structures where they’re difficult to remove), you can lessen the chances of bird’s nest fungi appearing in your yard by raking the soil frequently, decreasing irrigation in shady areas, and using living mulches and edible ground covers (instead of arborist wood chips) in your garden beds.

Fungicide should never be used, as it could disrupt the natural processes in your ecosystem.

View the Web Story on bird’s nest fungus.

This post updated from an article that originally appeared on January 15, 2015.

Wow, this is amazing! I had no idea fungi could grow in such intricate shapes. The nest-like structure of this fungus is absolutely fascinating. As a gardener, I’m always on the lookout for unique and interesting plants to add to my garden, and this certainly fits the bill. Thanks for sharing!

Found them in my yard today! Didn’t know what they were until a neighbor on Nextdoor told me. Very interesting lil fungi. I thought maybe they had been some type of insect eggs. ♀️I’m in Washington State.

I have some in my raised garden bed if someone wants them I live in indiana

Just a heads up, the sheer number of ads on your side ton’t allow this page to be opened on a regular internet connection without locking up and shutting down the program. Tried it at my house, at my parents out of curiosity. Failed.

On the campus connection it works….slowly. I’m guessing all the people posting have ad blocks, so you’re not profiting from them, but for the rest of us your site won’t even work, which defeats the purpose of a site like this and ad generated income.

We are trying to grow this variety for pancreatic cancer research. Do you know what your mulch is made of? Type of tree bark, organic mixtures, moisture levels? Anything information would be of great assistance. If you see them this year would you please contact us? Take a sample

Where are you? ONe of the students in Joe Lamp’l Tomato class found these and did some research. You should make contact and ask them to save seeds for you. WE LOVE SHARING SEEDS!

(growing a greener world, joegardener.com)

I have tons of these that grew out of the Scott’s brand of brown wood mulch sold at Home Depot. Zone 7A7B Cobb County, GA. We have been getting lots of rain and substantial heat that could be pulled up for June and July. I put in 60 bags Memorial Day weekend for a pine/poplar morning sun and afternoon shade yard. The birds nest fungi is thriving and spreading all over. It popped up early July.

Dan,

I came across a similar one in my garden this morning. Black seed, creamy exterior. I had never seen it before, so I began looking online into its edibility/medicinal properties and came across this. I can send a pic to your email if you’d like to view. I used cypress shavings as mulch last year and routinely put rabbit manure in the garden. I hope this helps. I’ll attach my email or you can view the pictures on my facebook page: Natasha’s Nature. Good luck in your research.

OMG-same here! I live in Cobb County and this birds nest fungi is taking over and it’s disgusting (in my opinion). Are you leaving it to grow and controlling it somehow?

I have recently noticed quite a bit of these growing in my raised garden beds this year for the first time. Interesting enough I did not mulch my beds this year. However, I have the past two years and there are bits decomposing now. In the past I have always purchased mulch from Lowes. It was the Superior Cedar Products 100% Virgin Cedar Mulch.

I have a bunch of these just pop up in my yard you can come get them all if you like. I live at bluescanoelivery.com ask for Kathy Caudill found birdnest mushrooms in Indiana

I am in Ohio. Have it all over in the part of my yard newly covered in wood chips from the grounded down stumps of the trees that were cut down. Mulberry trees. The part of the yard with moderate shade most the day with about 2 hour window of light before the sun sets behind the trees. There is a lot of it here right now. It’s in all stages of life. New sprouts, dead ones and ones in their prime. Won’t last long.

I’m here in Fajardo Puerto Rico and I have a lot of this growing in red wood chips in our front herb garden. I photographed and researched trying to find out exactly what I was looking at when I discovered it’s birds nest fungus. The only annoying part is that as the mass has grown under and throughout my herbs such as culantro and basil, the little black spores attach to the leaves and are extremely difficult to remove. Right now I’m spraying the plants down with soap water mix.

Can you tell me where I can buy some birds nest mushrooms?

I’m not sure, as they grow naturally in my mulch.

I can send you some of the mushrooms, I was actually planning on making a small garden with the since I had a handful of them.

We have these all through our lawn at the moment, do we just let it go or start pulling them out? Our kids play outside so was just wanting to know what to do?

Thanks

They’re not harmful so I’d just leave them be unless you want to pull them for aesthetic reasons.

do these have any animal/insects in them? are they harmful to my flowers?

They’re a harmless fungi as far as I know.

Hi-I understand these are harmless but it has grown like wildfire all over my yard, front and back, and it looks disgusting and when you pull it up, there’s thick white stuff and I want to get rid of it or at least minimize the spreading of it. Any suggestions?

How do you fix them to eat? They are so cute and would look good on a plate but not sure what you mean that they are edible.

As stated in my post: “Bird’s nest fungi are considered inedible due to their tiny size, though no study has ever shown them to be poisonous.” So I did not say they are edible, though they won’t harm you either. They’re simply considered too small to be a useful or interesting food.

AKA splash cups, these mushrooms look like little nests. Splish Splash: Bird’s Nest Fungi http://t.co/rq6FjzWWLG < TY for RT! @BG_garden

Viva la Bird’s Nest Fungi–the photos are gorgeous! The metallic colors are irresistible!

A bizarre name for a mushroom until you actually see it. Splish Splash: Bird’s Nest Fungi http://t.co/j7pQI0s5bT #gardenchat

Water drops will launch the “eggs” into the air! Splish Splash: Bird’s Nest Fungi http://t.co/nUv2MeGDDA #gardenchat #mycology

They look like egg-filled nests, but they’re actually mushrooms! Splish Splash: Bird’s Nest Fungi http://t.co/xpgmlvZF0a #mycology

These are amazing!

Have you ever seen Birds Nest Fungi? Unique in every sense. More here: http://t.co/oBzcucHy44

RT @theGardenBetty: Also known as splash cups, these mushrooms look like little nests. Splish Splash: Bird’s Nest Fungi http://t.co/rq6FjzW…

Also known as splash cups, these mushrooms look like little nests. Splish Splash: Bird’s Nest Fungi http://t.co/rq6FjzWWLG #gardenchat

These mushrooms disperse through the power of raindrops. Splish Splash: Bird’s Nest Fungi http://t.co/lEUAAzk5r9 #gardenchat

I have these all over a corner of our yard after putting mulch down. Thank you for the information! I had no idea what they were.

Hi Linda,

Thank you for sharing such a curious nature’s creation. They do look like river pebbles. They also remind me of black pearls or beans.

I wonder, can you use their caps (after they are done with them) to put some seed starter and plant seeds for this year’s garden?

Kimberly

The caps are tiny, only a centimeter in diameter, so they would barely hold a seed. 🙂 I’ve never seen bird’s nest fungi grow any larger than these.

Oh my! They are really tiny. The eggs must be just a couple of millimeters wide. You took really nice pictures of them.

Fascinating biology for such tiny little mushrooms. Splish Splash: Bird’s Nest Fungi http://t.co/426CKLzHDI #gardenchat #mycology

Blogged on Garden Betty: Splish Splash: Bird’s Nest Fungi http://t.co/3kLRKWxQg5