Up until last week, when I spent a few days exploring north-central Arizona, I really had no idea that the forests around Flagstaff were so green and volcanic. Had it not been for red rock mesas rising in the distance and tumbleweeds rolling across the desert, I wouldn’t have thought we were in the state best known for the Grand Canyon. (Then again, Arizona has surprised me before with fantastic waterfalls I’ve never seen anywhere else.)

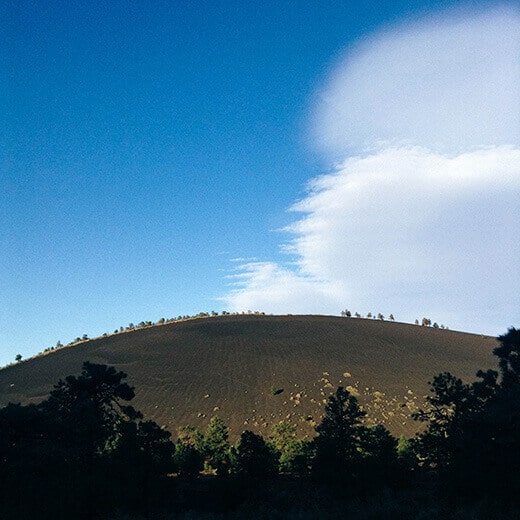

The region between Sunset Crater Volcano and Wupatki National Monuments is known for its imposing cinder cones, the youngest of which is Sunset Crater itself.

Sunset Crater belongs to a string of volcanoes in the San Francisco Volcanic Field, which comprises about 600 volcanoes that range in age from 6 million years old to 1,000 years old. Since Sunset Crater is so young, it’s off limits to hiking because it’s still being studied. Scientists consider it dormant, not extinct.

When it erupted, fire spewed over 850 feet high and ash blanketed an area covering 64,000 acres. The eruption buried forests and farms and forced the abandonment of the local Sinagua settlements. Substantial lava flows still remain at the base of Sunset Crater and at one time there was even a lava tube accessible to hikers, but it was closed after a partial collapse.

The area has started to revegetate with wildflowers and pines, and mounds of volcanic cinders (which act as a natural mulch and source of nutrients) undulate across the landscape, looking like massive sand dunes.

The region is so thick with cinder cones that parts of it are open to off-roading (the Cinder Hills OHV Area). I saw so many tracks running up and down the cones, some that were 1,000 feet high or more. They loomed above ponderosa pines in the middle of Coconino National Forest, the inky black cinders gleaming against a canvas of brilliant blue sky.

On the other side of the San Francisco Peaks (an extinct stratovolcano complex that splits the northern section of the forest) lies the Lava River Cave. It is the longest cave of its kind — an ancient lava tube, to be exact — found in Arizona.

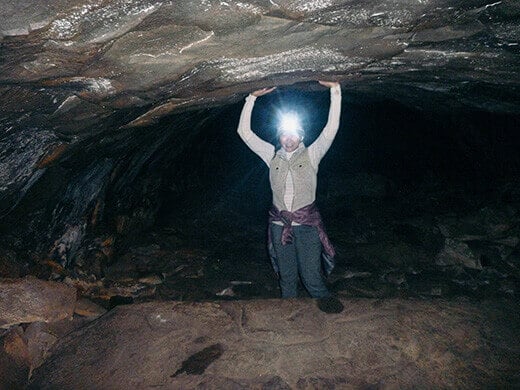

A lava tube is an underground channel through which molten lava used to flow. Over time, the lava ceases flowing and any lava remaining cools and hardens into rock. The channel turns into a cave, and in this case, the Lava River Cave is a three-quarter-mile long tunnel accessible from above ground.

Signs will warn you that temperatures inside the cave stay a constant 34°F to 40°F, making it chilly even in summer, but when we visited last week it was actually warmer than the outside air! The weather seemed to turn overnight in the Flagstaff region (while we were tent camping, no less) and we ended up driving through the first snowfall of the season to reach the cave.

It was so bizarre to find the entrance tucked into a stand of tall pines, marked off by giant stones leading into nothing but darkness.

The Lava River Cave formed about 700,000 years ago from an eruption in nearby Hart Prairie. It is an out-and-back hike through a tube that at its highest point is 30 feet tall, and its lowest point only 3 feet tall. Some parts are so rocky that they require a bit of scrambling, while others are so smooth it almost seems like they were paved. At the very end, there’s a chamber that continues even deeper but with an opening only 1 to 2 feet around, I can’t imagine what creepy crawlies might be lurking inside it.

The air inside the cave is crisp and cool, and at times my own breath kept blocking my headlamp-illuminated view of the path. About a third of the way in, the cave splits and meets up again. We took both paths (once on the way in, once on the way out), and found that one of them (the left fork going in) was much easier to navigate than the other. There were times when we’d be shuffling along the ancient lava bed, one hand above our heads to feel for impending ceiling drops, and suddenly we’d find ourselves nearly crawling along the 3-foot-high tunnel.

I have to say that the length of the lava tube hike was perfect — I think claustrophobia would start to set in after a couple of miles. At one point Will and I both turned off our lamps for a few seconds and found ourselves enveloped in a shroud of pitch black silence. The sheer sensory deprivation was bizarre!

All in all, it was a totally different and fun little adventure. Volcanoes, lava flows, and lava tubes in Arizona… who knew?

You are such an amazing writer! Great story.

Thank you so much for the kind comment!

There are dormant volcanoes in the state… who knew? Volcanoes, Lava Flows, and Lava Tubes in Arizona http://t.co/f1YGGALI4k #adventure

In the Flagstaff region alone, there are over 600 volcanoes! Volcanoes, Lava Flows, and Lava Tubes in Arizona http://t.co/ux73l0ZA0y #travel

Exploring north-central Arizona’s volcanic landscape. Volcanoes, Lava Flows, and Lava Tubes in Arizona http://t.co/LqfXUR3s2p #adventure

Volcanoes, Lava Flows, and Lava Tubes in Arizona | Garden Betty http://t.co/pcWEcnc2Mw

Until my visit, I had no idea Flagstaff was so green and volcanic. Volcanoes, Lava Flows, and Lava Tubes in Arizona http://t.co/S1XnTKFuNp

All this from a state best known for the Grand Canyon. Volcanoes, Lava Flows, and Lava Tubes in Arizona http://t.co/qttHVux6TW #adventure

Great photos! I’m always looking for interesting hikes. If I ever get back to that area, I will check out Lava River Cave.

You must! It’s so neat that something like that still exists (especially in a place you wouldn’t ordinarily think of).

Blogged on Garden Betty: Volcanoes, Lava Flows, and Lava Tubes in Arizona http://t.co/zpbrcCtCuc